Welcome To The Ryan Gosling Freak Show - Esquire - 2011 (September)

This article is from the magazine Esquire, dated September 2011, featuring Ryan Gosling.

The high-res magazine scans are from StoreMags.com. The additional pictures at the bottom are from Fashion Fame.

Welcome To The Ryan Gosling Freak Show

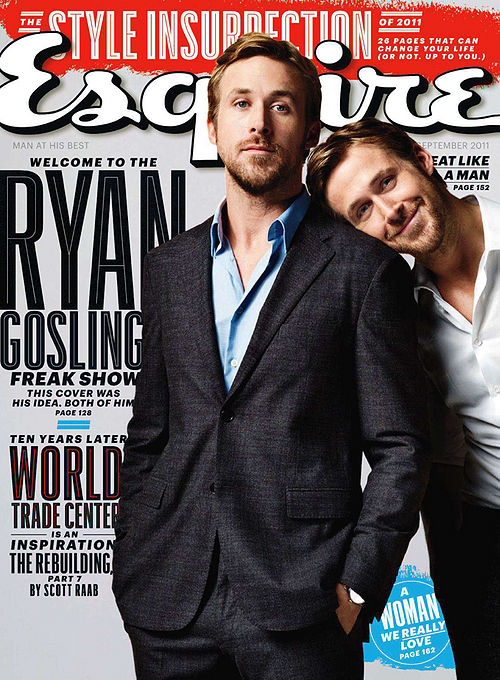

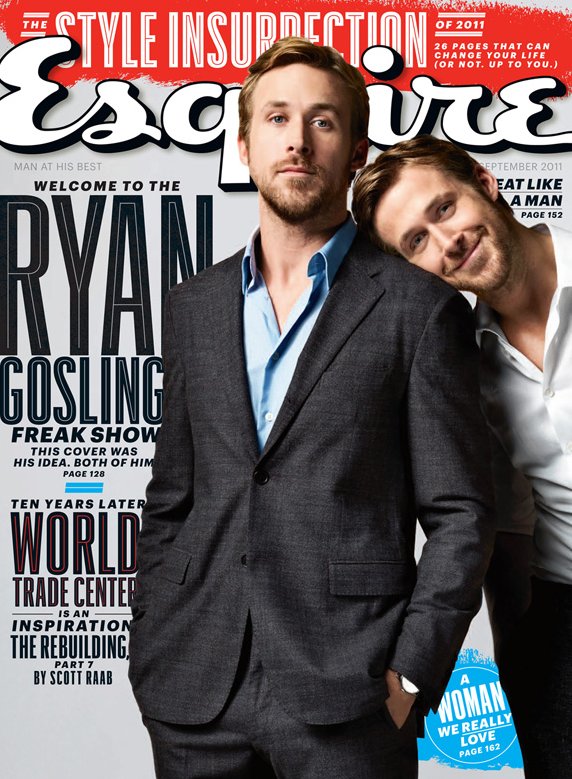

Ryan Gosling covers September 2011 issue of Esquire magazine. Esquire gives double dose of Ryan who is looking dapper in a suit.

Freak Show, With Ryan Gosling: Take a road trip with a movie star everyone recognizes but can't quite name - a man of many parts, strange tastes, and manic inventiveness. He's brought masks for the ride. And crazy skills behind the wheel.

Gosling Makes A Diorama: After their time together (see page 128), Ryan Gosling gave writer at large Tom Chiarella a present: this homemade diorama, which, when you look into it, is a representation of his childhood home, which was haunted.

1. When you plug in the box, a string of Christmas lights illuminates the inside, revealing a haunted house, a cemetery, and even a small tree.

2. Gosling included an unlabeled CD and the instruction "Play." It's an obscure album called Ghetto Reality, recorded in 1969 by a Rochester, New York, elementary-school teacher, Nancy Dupree, and her music students.

3. Questions ("Are you aware of being looked at?" "What is it with you and bones?") and drawings Gosling cut out of Chiarella's notebook.

4. Matches, a strike board, and cigarettes, which are used to cover the scene inside in a smoky haze.

5. Always practical (and safe!), Gosling wrote a warning on the back of the box: "Do not leave plugged in."

Welcome To Goslingland

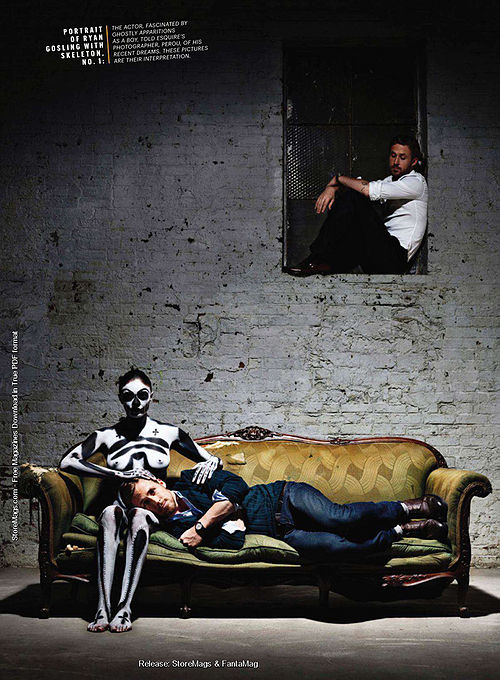

A long ride through a dangerous world of skeletons, roller coasters, fast cars, slow talk, Bonkers candy, street crawlers, love parades, and freak shows, with Ryan Gosling, the most amused man in movies.

By Tom Chiarella

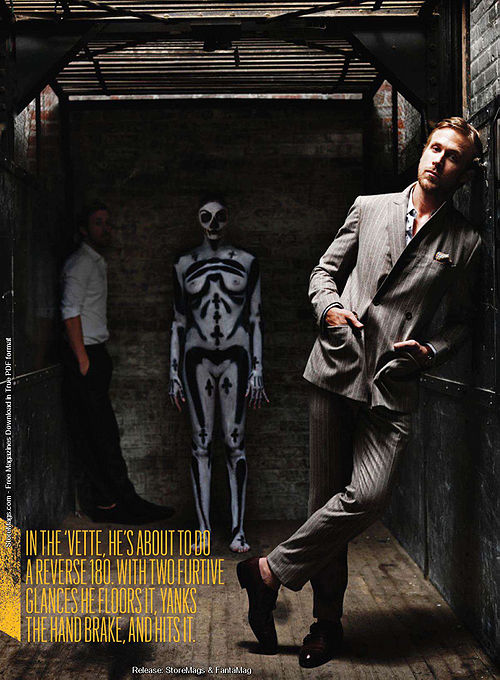

Photographs by Peru

In collaboration with Ryan Gosling

4:08 P.M. - Greenwich Village - First thing: Yes, Ryan Gosling will drive. It's a Corvette - red one, too, sassy and low-slung, waiting for him curbside, gripping the crosstown street like a muscle. The afternoon air gets throaty and wet with the deep ticking of that engine. That's not to say Gosling doesn't make an effort to share the wealth - a sports car with traction control, muffler disengaged, and a Friday with no particular place to go - such as it is.

So he proffers the key fob. He says, "You wanna drive?" as if he, the appointed wheelman of the night, doesn't know better. "I'm really not even sure where we're going." But that's easy. One big loop: down the FDR, through the Battery Tunnel to Brooklyn, then along the curl of the Belt Parkway past Sheepshead Bay and Canarsie to a distant, sometimes empty, part-time police training yard and park where he will undertake a little stunt driving. The reason for this: He reincarnates Steve McQueen as an anesthetized hipster and innocent face-stomper in the pulse-y new chase-fable Drive (out September 16), and he learned his own stunts for the role. He's going to show off a few, and after that it's back to Manhattan. This being Friday, suburban day off thanks-to-God, and this being 4:00 P.M., the penultimate analog tick of the workweek, even a newly minted New Yorker like Ryan Gosling knows: Outbound traffic will be murder.

He's brought a mask, pinched in his fingertips, as a gift. A fox. "I light this neighborhood," he says before he rolls the car eastward from it's flashered double-park, "because I'm lucky enough to have easy access to not one but two Halloween stores. I bought a bunch of masks yesterday." Gosling shows a curious reverence for certain traditional supernatural icons - ghosts, skeletons, hauntings in general. For weeks he has exchanged e-mails with the photographer who took the pictures for this story, hoping to direct the shoot as a means of exploring his self-revelations. But he doesn't particularly want converts. He taps the nose of this fox after he's given it away, smiles, and says, "You don't have to wear it."

Last year Gosling, who is thirty, became a star by way of an indie flick that went relatively huge, Blue Valentine, in which he played Dean, the drunk housepainter and half-decent father, pitching the guy's emotional caterwaulings in a maleness both grand and petty. This summer he stepped into a big-budget comedy as a self-obsessed man-coach opposite Steve Carell in Crazy, Stupid, Love. He's bearded on this day, and in this way he's maybe most like young Noah Calhoun, his character in The Notebook. Oh, The Notebook! The one movie that allows people to dredge his persona from the recesses of their long-term memory, to unloose his name from their palate. The name, the word, the sight of his face, get lost in there without The Notebook as reference. If the wooden three-day romance of Titanic matters in the least, then The Notebook may be the most important movie of the first half of this century. It sure works to locate this guy, anyway. Everybody knows Ryan Gosling the very moment that movie is mentioned. It doesn't seem to bother him. He seems to be always on the verge of laughing, of really cracking up.

"So I figure this will be kind of a road trip," Gosling says, as if the nature of any moment were a simple question of it being coaxed. "We'll look for an adventure, right?"

4:28 P.M. - Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel - Lights scalloping past on the tile ceiling, and Ryan Gosling reveals: his apartment is full of skeletons. "I give them nervous systems made from Christmas lights." He uses that word, give, as if he were rescuing them, applying some homemade splint. He pulls out his phone, thumbs his way through his photos, and says, "Look." It is the second floor of his apartment, and there is a skeleton, bone white and incandescent, standing, or hanging somehow in the window. "I made the table, too," Gosling says. "From a church door."

Seen from the passenger seat, he's somehow slight and earnest, young-looking. Slick down his hair and comb him over and he'd echo himself as the young Mouseketeer from the Disney revival of The Mickey Mouse Club, which he starred in alongside Justin Timberlake, Christina Aguilera, and Britney Spears in the early nineties. The soft timbre of his voice, the demeanor of humble quietude, there in the fleshlight grip of the car's snug interior, bring to mind Lars from Lars and the Real Girl, a guy harboring a plaintive and ever-evolving love for a sex foll. That one came close on the heels of his Academy Award nomination for his role as a crack-addicted teacher in Half-Nelson. These two men share a few things with their creator, in that they are indelicate, stronger than you think, and quiet to a fault.

5:14 P.M. - Floyd Bennett Field, Across Flatbush Avenue from Dead Horse Bay - Gosling prowls the lot. He looks left, at the rows of cars parked by what looks like a school. He's unfazed by the sight of a school bus on the other side of the same parking lot, or by the watchful parents standing, hands on hips. There isn't a great deal of fear in him, which is not to suggest that he's particularly cool of aloof or that he shows no judgement. He knows cars, having himself rebuilt the car he commanded in Drive while working at a garage in Hollywood. "It took forever," Gosling says. "This guy Pedro would sit there and tell me what to do, but he wouldn't touch the car. He just barked orders, and I followed them. But when we get to the transmission, he replaced the whole thing without telling me. I was angry, upset. I got all teared up. And Pedro said, 'I just put that transmission up in there because I had to get some real jobs in here.' I respected that, but I told him, 'I have one chance in my life to take the time to learn this.'"

Right now, in the Corvette, he's about to do a reverse 180, and with two furtive glances he floors it in reverse, finds his speed, then, yanking the hand brake and twisting the wheel hard to the left, he hits it. The car pushes itself into a small, tight curl, which sloshes every bit of the self hard into the cold inside of the passenger door. It hurts, it makes you laugh, it makes you search for words to describe it. Gosling cannot help himself; he laughs. He jabs at the radio. "I think we did that to Trisha Yearwood," he says. This, all of this, makes him smile, a big burning movie-star smile.

The driving event is over at 5:35. That's when Ryan Gosling asks, "You want to go to Coney Island?"

6:19 P.M. - 7-Eleven Store, Knapp Street, Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn - Know this much about Ryan Gosling: Man loves candy. He speaks of it the way rich men discuss wine; he picks it from the shelves like he's working piano keys. He knows where it lives in the racks - low or high, above what display, betwixt whatever chocolates squat there. (Gosling has no use for chocolate.) Five stops at bodegas, and one at this 7-Eleven, and in each case Ryan Gosling sniffs out the florid Japanese gelatin as if he lived on the block, as if he shopped there every damned day. Its very presence seems to comfort him. "This is the stuff," he says, in aisle two of four. Then he piles them on the countertop. Kazoozles atop Nerds Ropes, twin packs of Hi-Chews, green apple and grape. He also feels strongly about Haribos, especially the multiflavored bag. "I like to call this the next level of candy," he says, with a thready graveness in his voice either mocking seriousness or giving, in fact, a serious mocking. Over and over again, he uses his eyes to say: Are you with me? More enthusiasm, even as he goes on. "Hi-chews! Look at these! It's the candy that never quits on you. This candy is always worth the price. There used to be a candy called Bonkers, which I believe to be the greatest candy of all time." He pours coffee for both of us, with as much sugar as he can get in, and turns to the register before he continues. A girl stands at one end of the aisle, holding her phone up for a photo of him unaware. "For some reason, they discontinued Bonkers. These are good, you'll see," he says, holding up the Hi-Chews. Then he hands me my coffee and says with a smile, "Sugar till you die."

The girl moves the camera from in front of her face. "Can I take a picture of you?" she asks.

Gosling finishes his thought: "But that fact alone doesn't really justify the end of Bonkers." Then he turns back to the girl, who gropes for his name and hands me her camera. Gosling stands with his arm around her. "I know your name," she says, tilting her head in defeat. "I really do."

Gosling turns back to me. "Sometimes I think that the one thing I love most about being an adult is the right to buy candy whenever and wherever I want," he says. Then he asks the girl, "Which way to Coney Island?"

Her hand drops to her side, and she smiles and says, "Oh, I know! You're Paul Bettany."

6:58 P.M. - Coney Island Amusement Park, West Twelfth Street off Surf Avenue - The streets are yellow with a long, long sunset, so that everything looks like it was sand once. The place is not deserted - the park is open, but it's fair to say no one's here. The roller coaster clatters upward in front of us. Gosling watches it, jaw tightened. He always looks like he's looking up and out, as if the would were this kind of rising spectacle. Then he yanks the parking brake and asks, "If you could create a theme park, what would your theme be?" He quarter-turns his head and waits for an answer.

It's hard to accept that he's really asking, that he isn't just finding a way to turn the Q&A tables by making an excuse to unveil his own idea. He means it. He wants the answer. The notion dawns that Gosling is a seeker. He doesn't give a shit what seems naive. The answers to a child's questions matter to him, and he wants to hear visions, because he grew up in one that no one believed in but him. And once they finally did, he went to work for Disney. That just made it more vivid.

I went through puberty in a theme park," he says. He means Disney World, his stint as a Mouseketeer. "I'm grateful. That place was a landscape to me. I had adventures every day." So none of the world-weary adult warnings about Disneyfication and corporate middle-of-the-roaddom from him. "Backstage at Disney World, there are stories. Mickey Mouse with his head off, drinking coffee on break. Pirates on the phone. Ghosts in line for food. It just made me see things."

This is Coney Island: Walk the boardwalk, stroll to the water's edge, climb a lifeguard chair, not a soul on the beach. Gosling eats Kazoozles. He swears by them some more, then says, "My theme park would be a theme park about living in a theme park." Like a behind-the-scenes thing? "Sort of more like the life I've lived so far," he says. Finally, Gosling jumps off the chair into the sand, jogs to the water, picks his way out to the end of a jetty, and appears to take a leak. He faces the huge, boatless expanse with his hands on his hips, so that from behind he might just be some guy regarding the ocean as if the whole thing were his - a colonial explorer, or a workaday Joe, playing hooky from the office and feeling human.

"I failed," he says. "Too much pressure, even though nobody's watching. I gotta find a john." He sips up and turns his back on the sea.

8:04 P.M. - Water-Gun Shooting Gallery, Coney Island - The key to everything is The Notebook. At Coney - and that's what they call it, the kids who work there, sixteen-, seventeen-, eighteen-year-old black kids in matching polo shirts and cheap baseball hats, working their summers, leaning into long nights in sight of the ocean, nagging out time until school starts again - just plain Coney, as in "You! What are you doing at Coney? You. I know you. Who are you? Let me think. Damn. Tariq, who is he? I know you, right? You a movie star, right? I just can't. What movie you in? Damn. What is your name? Why you at Coney all the sudden?"

Through all this, Gosling smiles and nods. He;s got some bits, some automatic responses: I just have one of those faces, or People say that all the time. But he never says his name, never gives it away. Not that he's being difficult. He seems to enjoy passing through this world as a vaguer representation of himself. But he's not diffident or deceptive. He signs autographs freely, doles out hugs, poses for more phone photos in one visit to the amusement park than most people do in a year. He's affable about being recognized but not named. He really does have one of those faces. "It's like being in a dream. You don't know anybody, but everybody knows you, everybody reacts to you. You can be walking along in a dream, through a pretty normal world, and then bam, everything seems to be a response to your presence. Everything seems to be driven by you. And that's notable at first, and you deal with it. And then - and it happens every time - you become aware it's a dream. Right about then, when you think you have it figured, and that acknowledging that will make it easier, it inevitably becomes a nightmare."

This thing, this event at Coney, is nowhere near that stage. These kids are giving him plenty of room, killing time chatting it up with the movie star they can't name. Mention of Blue Valentine does them no good. Half Nelson? The Believer? None of that works. The best hint involves one little finger tap on the spiral ring of a sketchpad, to a kid begging for a hint. "Notebook? That's that mean? Notebook. What's... notebook! Notebook! I know him. He's from the Notebook!"

Everyone knows The Notebook. Every teenager on the midway has seen it, a movie that is half as old now as they are, a gauzy fable about the fated love of two white people in North Carolina sixty-five years ago. They all tell him, too: "That's a good movie."

Tariq comes over from his position at the Wac-A-Mole stand, takes a long look at Gosling, and says, "That's Ryan Reynolds."

The key to everything is the notebook. Purchased at Target, bearing a mere six questions for Ryan Gosling, an unfinished list carried on what was scheduled as a two hour interview but is slowly becoming a long day's journey into night. "That's with the skeletons?" being the best question of them all. There are also sketches of skeletons in the notebook, vodka-driven, drawn on my plane rise out - I had heard about his conversations with our photographer, and so I drew skeletons. Two pages. That's it. At Coney, Ryan Gosling takes the notebook. He says he will answer the questions (He did answer these questions, in his way, turning the notebook into an interactive art project. Experience it on page 46 or on the iPad).

Vaguely labeled T-shirt, utterly blank zip-up sweatshirt, ball cap, blue jeans, Gosling is after the Cyclone, the wooden roller coaster most often associated with Coney Island. He's not afraid. He grew up around them; he's been on plenty of rides in his life. He just wants to understand that fear. "What's the fear? That you'll fall? Is it the transition of speeds? The suddenly-moving-very-fast thing? Fear of the heights? Is it fear of incompetence? Do you think it will just fly off the tracks?"

The answers don't matter. His questions are telling, of course. He doesn't ask out of his own fear - he understands what it is to get up very high, to give in to the speed of things, to watch the world whipping by. He wants confirmation of the vision.

On the Cyclone, Gosling sits in the backseat and screams, dully and at the top of his lungs. He films the event with his phone. "It looked pretty scary," he says, "watching you with your eyes closed."

His screaming, he is told, made it scarier.

This makes him laugh. "I was trying to help. I wanted you to think there was someone more scared than you, someone who saw it your way."

10:37 P.M. - Panna II Restaurant, back in Manhattan - Under a heavy sea of Christmas lights at an Indian restaurant, Ryan Gosling tells the story of his childhood experience with the supernatural. It isn't spooky, and he tells it in a heavily boiled-down manner, without a hint of flourish. When he was young, very young, like four, living with his family in Cornwall, Ontario, he thought he saw an old man in his house: "He just sat. And I knew from a very young ange that he was a ghost, too. He scared me. I told my mother, but she couldn't see him. Nobody could. And I learned to live with that. I had to. Then, a few years later, she thought she saw him, then almost right away my cousin saw him, and then my uncle. And we were outta there in fairly short order. So my mom said she saw the ghost, but she was also obsessed with Zelda and Lord of the Rings, so you have to take that with a grain of salt. I don't believe I saw a ghost. I don't believe my house was haunted. I think I had an overactive imagination and I was so convinced that those around me became convinced, too. I don't believe in ghosts."

More than any mentor, he says, or any actin teacher or grown up, that feeling - of being different but also, bu necessity, the same as everyone around him, taught him.

"I think I was always bound to become two selves, if I wasn't already," he says. "Now there's this me, this public me, and I know that I have become two people. This is what I told the photographer before he took those photographs. Even my own name sounds like just someone I know."

2:06 A.M. - East Fifth Street near Avenue B - The ghosts and skeletons of the night walk the streets of New York starting about now. Small bands approach, booze-weary men arm in arm, party-dressed women with purses dangling from cocked arms, heads down, checking the dark sidewalk for heel traps.

Block after block, Ryan Gosling walks. It's late, the last hours of an unintentional road trip to nowhere, and no one seems to recognize him, just so long as he keeps moving. It's been nothing but walking for almost three hours. The streets are unusually festive, even for the East Village, even at two in the morning. Gosling always seems to be walking to the edge of one type of circus or another. "I though this was just going to be one event," he says of the evening, now stretched through the night, into morning. "Just the drive and a few stunts. It just keeps building, one event, then another."

At the corner, waiting for the light, three transgendered citizens take notice of him. The first - clearly once, or soon to be, a very short bodybuilding man - asks Gosling if he'd pose for a picture. Gosling agrees. It is literally the forty-seventh photograph he's agreed to be in tonight. In this way, one supposes, the dream becomes the nightmare. "You know," the little man says, "gay marriage was legalized by New York State tonight." It's true - the news broke somewhere between Coney Island and now, apparently. "That's great," Gosling says. "I hadn't heard."

"You should jump in my arms. We should get a picture of that for tonight!"

Gosling laughs and shakes his head.

"I'd like to put you in my pocket and carry you around," the little man says.

"I'd let you," Gosling says, "but I don't know you that well."

"Don't worry so much," the man says. Then Gosling smiles and waves his own way on into the night.

2:55 A.M. - East Seventh Street between First Avenue and Avenue A - Just about at the end of things, Ryan Gosling stands at the curb, square in front of the Corvette, and declares that he doesn't want to get in. Not anymore. Earlier he was game, plenty game. But it's late, and surely the night is almost quit - he wants to leave the car where it is. "We don't need it," he says. "A car is only trouble, at a certain point." Hands dipped to the knuckles in the pockets of his unremarkable jeans, wrist looped through a plastic bag sunk in the summer air, dangling against the weight of two unfinished packs of candy, a fifteen-dollar pack of cigarettes, a black Bic lighter - the detritus of now-and-again bodega stops over the last several hours, loop after loop through the lower third of the island. Gosling's just moved to New York. The guy doesn't want to quit.

Fair enough. The walking continues. And Ryan Gosling keeps on, walking, talking. He rambles: the Congo, Disney World, Canada, downtown L.A. He casts a glance at the distance, here defined by the net of darkness that hangs at the end of a halfblock of streetlights spotlighting the uneven sidewalks, the doorways varnished with cheap paint, the mouth of one alley or another. No matter how close he stands, Gosling always seems to be looking at a distant point. It's a guiltless, unassuming gaze, a little stoned or a little dreamy."The road trip isn't over," Gosling says, loud enough for it to be an exclamation, loud enough that he sounds either hopeful and like a boy who doesn't know any better, or wizened and ironic, like someone who knows better than a boy. It mostly depends on how you take him in.