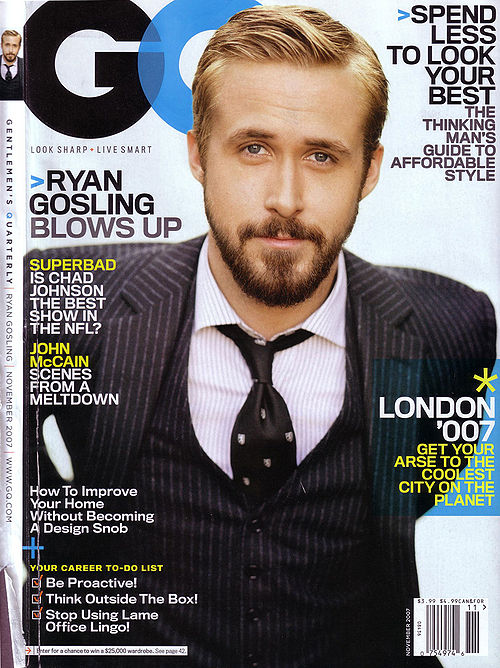

The Loner - GQ - 2007 (November)

This article is from the magazine GQ, dated November 2007.

The high-res magazine scans are from Gosling Fan. The additional pictures at the bottom are from GQ.com.

The Loner

Ryan Gosling wants to hide from us. He plays weirdos and sociopaths in small-budget films. He guards his personal life fiercely. He's never in the gossip rags. So how did he get this famous? By being one of the finest actors of our time, for starters.

By Alex Pappademas

Photographs by Nathaniel Goldberg

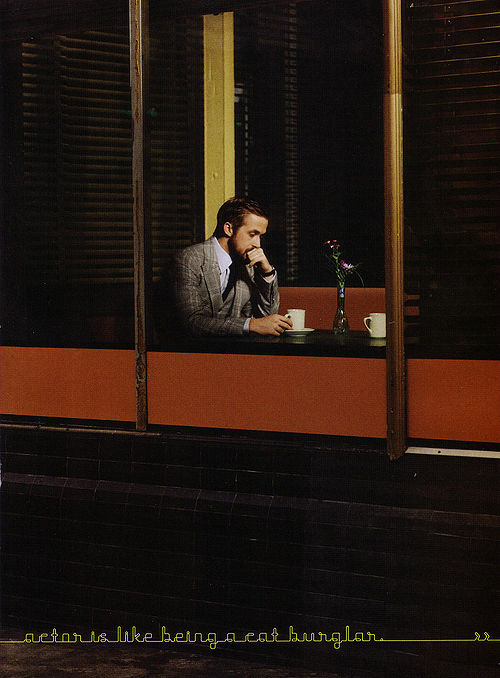

In photographs, Ryan Gosling often appears to be in the early stages of cultivating Frank Serpico's beard, but today he's looking almost altar-boyishly presentable—hair neatly combed, facial scruff pruned.

He's sitting up straight in a post-modern-Stone-Age-Jetsons coffee shop in Hollywood. He comes here often, and the waitresses know he wants the meatloaf before he even orders it, and he watches them go, with a look that's more wistful than wolfish.

What was the question? Oh, right:

Gosling's staying in an apartment near here. He says he's been doing "experiments," and declines to elaborate. But until recently, he had a place in downtown Los Angeles. He moved there four years ago, back when downtown was where you moved if you wanted to be in L.A. but not of it, and I'd asked if that was part of its appeal.

"No, man," Gosling says. "I moved down there because you could do anything you wanted."

Back then, downtown was another city, Gosling says. An island of community amid L.A.'s lonely sprawl. You knew your neighbors. You knew the bums. It was sort of lawless, too:

"I started tagging," Gosling says. "I tried to start a battle. I'd heard if you tag over someone else's tag, you declare war. So I worked on my tag. Spray paint, stencils—I got down. And when I thought I was ready, I started tagging over some specific guys' [tags].

"Not one of them ever messed with me, man," he says. "Because my tag was so pathetic. Maybe they thought some drunk monkey got loose with a spray can."

Gosling's T-shirt is torn at the neck and faded to the point of translucence; his black boots are battered and pale with white dust, like he's been kicking drywall. His voice is a sinus-y rumble, a head cold caught from Dustin Hoffman, with a backspin of wiseguy how's-ya-mutha Brooklynese, which is charming but also incongruous coming from a Canadian. It makes him seem older than 26, or temporally displaced—a time traveler from the days when movie actors didn't speak with hey-dude flatness because they were not mere dudes, because they'd actually lived, slung hash, fought wars, fixed things when they broke. Gosling isn't one of those guys, but the essence of his appeal is that he seems like he could be.

He won't say what his tag was—he's worried the graffiti guys might read this, that he'll get his legs broken. It's probably not an issue. Gosling was hardly the first young creative type to move downtown, but in the past few years the area's been officially "discovered." The hipsters made it safe for the gallerists who made it safe for the developers. A thousand pricey live-work loft spaces bloomed. Now they give jaywalking tickets to the homeless down there. It's not the ghost town Gosling fell in love with—but he accepts what it's become.

"Nothing," Gosling says, "can stay like that forever."

This is a story about the gentrification of Ryan Gosling, acclaimed actor and failed vandal, who sought only to do whatever he wanted but has lately been feeling more fenced-in than ever. See, the idea behind this whole acting thing, initially, was that it represented an escape—from tiny Cornwall, Ontario, from school, from the Authority young Ryan had begun to exhibit Problems With. Eventually, Gosling realized acting could also be an excuse to investigate certain aspects of human nature he was curious about—the dark stuff, the stuff people did that didn't compute. He began seeking out characters who were troubled and wracked by contradiction. The neo-Nazi who's also Jewish in The Believer, the idealistic middle-school teacher with the crippling crack habit in Half Nelson, the baby-faced sociopath in—well, for a while there, he kinda had the market cornered on baby-faced sociopaths.

This was all fine. He even took parts in biggish movies—most recently Fracture, where he and Anthony Hopkins did the glossy legal-thriller thing, most famously 2004's swoony romance The Notebook. These were valuable experiences—it's not like Gosling's too good for legal thrillers or swoony romances, and doing them made him appreciate the freedom idiosyncratic shoestring-budgeted movies offer actors that much more.

But because Gosling's estimable charisma registered even in films that didn't exactly hang a light on it, and because his performances were marvels of unselfconscious animal instinct and fine-tuned craft—to the point that you usually didn't know where the animal ended and the fine-tuning began—his little movies still got attention, and Gosling got attention in them.

He's conducted himself the way you conduct yourself in Hollywood if all you're after is, at most, a small but noble patch of cult-actor grass to tend, a place in the heart of critics and video-store clerks, a good seat at the Independent Spirit Awards. And yet despite his best efforts, he's becoming a movie star. He's about to go shoot Peter Jackson's first post-Hobbit project, an adaptation of the best-selling novel The Lovely Bones. They are talking about him for the Captain Kirk part in the new Star Trek. He's gotten actor-of-his-generation props from both George Clooney and The New York Times.

He is famous.

He is also nervous. Because the one thing you generally don't get to do when you're famous is whatever you want.

Somebody wastes two bits playing the Doors' fervently stupid "Love Her Madly" on the jukebox, and Jim Morrison's fulminating fills the room like the smell of leather pants. Gosling begins riffing on Morrison in the manner in which he deserves to be riffed upon: "You're the Lizard King? Get outta here. Beat it. The coolest thing about the Doors is Apocalypse Now."

The only word for what he does with his meal when it arrives: He parses it. Subdivides the meatloaf into neat squares, carefully apportions cut-up green beans and gravied mashed potatoes. Then he talks about his childhood. He was mixed up, rules drove him crazy, he got into fights.

The radioactive spider at the center of this hero-origin story is the year his mom quit her job and home-schooled him. They burned through the fifth grade in a month, and Gosling spent the rest of the time pursuing a curriculum based on whatever interested him—drawing, the Beatles, Chet Baker, Bible movies. Meanwhile, his mom taught him to focus his rebellion. "She removed the mysterious cloak on arbitrary authority," Gosling says. "She was like, 'They're people; they should reason with you; if they don't, then you deserve more than that.' " An uncompromising artist was born.

But in the course of telling me all this, Gosling digresses and ends up telling me another tale from his youth. One that seems to explain as much as the home-schooling story does about why Gosling became who he became. One that involves sexually suggestive dancing.

In the beginning, Gosling had the Move: "One disgusting, filthy Move," he says, "that I built my empire on."

The beginning was a talent show, in which a girl for whom 7-year-old Gosling had a thing was performing an air-band version of Billy Joel's deathless class-struggle anthem "Uptown Girl." Hoping to get next to her, Gosling volunteered his services as a backup dancer. There was no choreography, so Gosling just did what he felt:

"I go up onstage and start, like, dry-humping the stage. I'm grabbing my stuff, I'm licking my fingers, I'm going up to grown women and trying to grind their faces. Meanwhile, I'm like, 7, y'know?"

You were 7—were you emulating behavior you'd seen somewhere else? On TV, maybe?

"No. I was just inherently filthy," Gosling says. "I was born inherently filthy. And then we won. And we got on the front page of the newspaper. And because I was so young, and what I was doing was so sexual, people really liked it. They really supported it. And then because I won that, I got on a TV show that was like Star Search. My parents were like, 'You have to come up with a real routine.' And—honestly—I said, 'That's what I do, it's my thing.' And they were like, 'But it's disgusting. You can't do that.' "

Were you aware that it was disgusting? Or did you think that if you were being rewarded for it, it was okay?

"Yeah," Gosling says. "In my little mind, I was giving the people what they wanted. Who are you, as my parents, to keep the people from getting their medicine, my filthy 7-year-old Move? I made up a routine that didn't have the Move in it. They locked me in the basement until I figured it out, and then they made me do it twice to make sure it was an actual routine. Then I went on the show—and I did the Move. And I won!"

So you were getting the wrong message.

"I was fighting the Man," Gosling says. "So then—are you interested in this?"

Totally.

"Okay," Gosling says, throwing one arm over the back of the booth. "Because it's the truth. I'm gonna tell you the truth."

He kept winning. People would see him on the streets of his little town, ask him to do the Move. With time the Move evolved: "It was very emotional," Gosling says. "The main thing was I would pick a girl, or a grown woman, from the audience, and I would just attack her sexually. I would make filthy love to her. I'd mock-take-off her clothes. I would show her what I, as a 7-year-old, would do to her if I could get her alone. The whole thing."

"I got kinda famous for it," he says. "I got beat up a lot for it, too. But it was worth it, because I knew it was my ticket outta there."

In his final appearance on the TV show, Gosling says, "I was facing these twin sisters. They were 8 years old. And they do 'Two Hearts,' the Phil Collins song. They're wearing heart outfits. Big pink heart-shaped bows in their hair. They do this beautiful tap routine. When they're done, they wait at the side of the stage, to psych me out. I look over—and they're both giving me the finger. These two little 8-year-olds with big heart bows on. So I go, ‘Man, I'm gonna show them.' And I went nuts. Filthy nuts. And I won."

You took it to the next level.

"Every time I did it," he says, "something great happened. I was kinda famous—Filthy Kid! Bring him to your party, he'll do the Move! I went to weddings and did the Move. I did it all."

I ask Gosling if he's exaggerated any of this for effect; he smiles and says this is how he remembers it. As foreshadowing, it's almost too perfect. A young man does the wrong thing, in public, and is rewarded for it, continuously and bewilderingly.

(Also: An eager 7-year-old throws his best approximation of grown-up sex-vibes at older women; dissolve to Gosling years later, at 21, squiring his Murder by Numbers costar Sandra Bullock, 37. The E! True Hollywood Story practically writes itself.)

Anyway: At some point, Gosling hears about a casting call for something called the All New Mickey Mouse Club and torments his parents until they agree to drive him to the audition. "I thought, If I could show this move to America"—he laughs—"I could build an empire. So I go to the Mickey Mouse Club audition, and I do the Move—and I get on the show."

The series is legendary now—a showbiz-kid Manhattan Project with a cast that included the precociously stage-parented likes of Justin Timberlake, Britney Spears, and Christina Aguilera. And what happened next was probably inevitable. The Mouse Club's producers told Gosling that under no circumstances, not over Walt's dead, possibly frozen body would he be allowed to do anything resembling the Move on the Disney Channel; then Gosling refused to learn to do anything else. They couldn't fire him—Gosling says they'd sunk too much money into promoting the presence of a Canadian in the cast—but they didn't do much else with him, either, and so he spent a couple of seasons dancing at the edge of the frame. Somebody like future 'NSYNC-er J.C. Chasez would be Gladys and he'd be a Pip.

Also, it turns out Mouseketeering didn't really pay. Gosling and his mom—who'd moved down to Florida with him when he got the show—lived in Kissimmee, in the part of the Yogi Bear Trailer Park that they called "Boo-Boo Harlem." Whatever he earned, they sent home. Still, it was show business. More important, it wasn't school. When he wasn't needed on the set, which was most of the time, Gosling rode Space Mountain, ate turkey legs at Epcot, sold his special employees-only Disney World day passes to families outside the park's gates. And when the show was canceled, he moved back to Canada determined to keep acting. It wasn't that he yearned for the spotlight; it just seemed like the most expedient route to a better life.

"I hated being a kid," he says. "A lot of kids feel like they got forced into being a child actor, but I wanted it, 'cause I wanted to be an adult."

Gosling did a bunch of kids' TV in Canada. Then he got the title role on Young Hercules—a show sprung from the sweaty foreheads of the same bold men behind Xena: Warrior Princess—and spent a couple of years in New Zealand, pretending to slay things in front of a green screen.

When he moved to Los Angeles—on his own at 16, crashing on couches—and started going on auditions for movies, he realized his résumé was problematic, consisting as it did of "The Mickey Mouse Club and me with a spear, fighting, like, a big phoenix. I couldn't get into a lot of rooms."

It took one movie to change that—The Believer, a fact-based drama about a teenage skinhead who's also a Jew. Gosling insists that it was the part, not him; that any knucklehead—a self-descriptor he's fond of—could have done what he did; that he threw himself into the role so completely out of gratitude to writer-director Henry Bean, who cast him even though he wasn't Jewish (or a Nazi).

The truth is Gosling had taken on a job that many other knuckleheads could easily have botched—for the movie to be something other than a tadpole Taxi Driver with a script-polish by O. Henry, the protagonist, Danny Balint, had to be many things at once. You had to buy him as self-loathing but full of untapped strength, and because the movie was about the seductiveness of power he had to be the kind of magnetic kid the dark side (represented by the reliably creepy Billy Zane as a professorial white supremacist) would be keen to seduce, which meant he had to be appealing as well as convincingly neo-Naziish.

Somehow Gosling managed; he made Balint, a walking metaphor, seem like a man in full. The movie won awards, got sold to Showtime, then September 11 happened and the movie got shelved for months, because, y'know, hate crimes. Too soon. Or something. But when people actually saw it, they got a glimpse of the staggering talent and presence Gosling possessed, and Gosling, who was happy to be making movies at all, got a taste of what it was like to make good ones.

"In everything I'd ever seen or read up until that point," he says, "it was like the writer was trying to make sense of life. And Henry wasn't doing that at all. It's rare to find a filmmaker who's ready to embrace the idea that it doesn't make sense and it never will, and [who] portrays his characters as trying to make sense of these things even though they can't. But because I had that experience on The Believer, I knew those movies were out there. I was searching for that feeling again after making that film."

Maybe he got spoiled right at the beginning. Maybe that's why so many of his films have been small and dark and little-seen—because chasing that feeling led naturally toward the squirmy and difficult.

Or there's the cynical read: Gosling needed to go this route, that his association with the Mouse, brief and unspectacular though it was, left him with a mark of teen-idol Cain he could shed only through indie-movie dues-paying.

Maybe, maybe not. The interesting thing about Gosling's work is that his performances in these un-teen films made ingenious use of all the qualities that would have made him a great teen idol—his physical confidence, his soothing demeanor, his goofy, earnest, fragile face. He's become a compelling actor not by burying that stuff but by twisting it, making it throw shadows, creating characters that possess Gosling-esque charisma but wear it like a mask—or a bulletproof vest.

Think of Dan Dunne from Half Nelson (the movie that got Gosling the chance to bring his mom to the Oscars, the year the Best Actor statue was Forest Whitaker's to lose). Dunne is an inveterate fuckup who keeps the world on his side using rumpled, soft-eyed charm (not unlike Gosling's own). Plenty of women smart enough to know that the real Dan Dunnes tend to break your heart and hock your iPod for dope money still walked out of that movie a-flutter with Ryan-love—which may be why all the creepy-guy performances in Gosling's filmography haven't made him any less attractive to mainstream Hollywood. After all, Brad Pitt used to play a lot of serial killers and nut jobs, too.

Our waitress appears, asks if we're doing okay. "We're okay," Gosling says. Then he says, "Are you okay?"

Again—somehow it comes off angelic. The boy can't help it.

Another Doors song in the background. Somebody in this coffee shop has decided to celebrate the lizard while enjoying some pie. Jim Morrison is killing the mood. Jim Morrison always kills the mood.

"People always say, 'Go make the Fractures so you can make your Half Nelsons'," Gosling says. "And the truth is, I got way more opportunities out of Half Nelson than I did out of Fracture. I've always been surprised at how many opportunities I've gotten out of the things I really believed in, versus the things I thought I should be doing.

"I've had actors that I really respect tell me, 'You've gotta surf-and-turf it in this town. One for them and one for you.' That's not true. It's really three for them and one for you. And not only that—if you do three for them, you've set a precedent. Any way you point yourself is where you're gonna go. If you point yourself in that direction, it's hard to ever come back."

That said, Gosling is a little worried about the direction he's pointed in now.

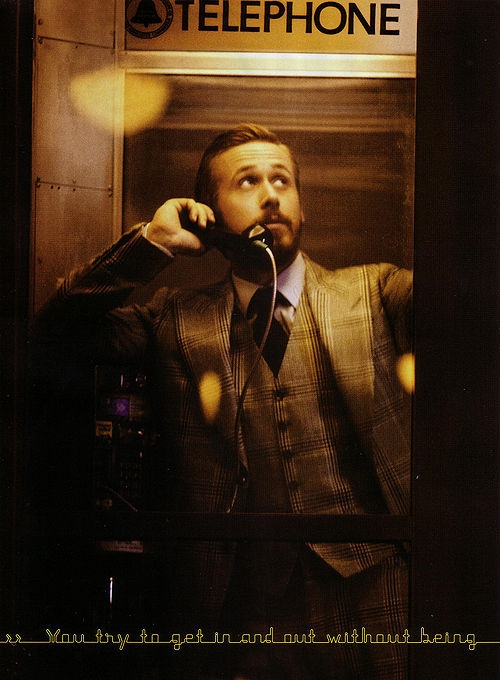

"Being an actor," he says, "is like being a cat burglar. You try to get in and out without being noticed. As soon as you get famous, it's like you've got a marching band with you every time you walk out of the house. And it's harder to make people believe you as a character. And your work goes downhill."

How do you guard against that?

"You got me," Gosling says. "I have no idea. There are people who are great at it. Like Chris Tucker. What do you know about Chris Tucker? That guy gets paid $25 million a movie. He's one of the biggest stars in the world. And I couldn't tell you anything about him. [laughs] Like, where does the guy live?"

I don't know. Here in Los Angeles, presumably.

"Presumably—but you don't know."

I don't. Is he friends with Ice Cube?

"You just think that. You don't know. You never saw them together. D'you know what the last thing Chris Tucker did was?"

Rush Hour 3?

"Rush Hour 3. You know what he did before Rush Hour 3?"

Rush Hour 2?

"You know what he did before that?"

Rush Hour?

"That's what I'm saying," Gosling says. "And outside of being a huge movie star, he seems to have no desire to be famous. I don't know anything about his personal life. I want some of that. You gotta admire people in this town that you don't know anything about. More people will see Rush Hour 3 than anything I ever do, but nobody's like, 'What's Chris Tucker up to?' So go ask Chris Tucker if you want to know how to do that, 'cause I haven't been able to do it."

He's aware of the swamp of contradictions in which this conversation has run aground. "Don't go on the cover of GQ and ask everyone to leave you alone," he says. "I think this movie's really special, and I want to do whatever I can to tell people about it, because I don't think it's something people are going to just run out and see. But, uh, yeah. As soon as you do something like this, you're provoking it. It's my own damn fault."

Sometime after The Notebook wrapped, Gosling and his costar Rachel McAdams started dating. The movie won them a Teen Choice Award for Best Kiss, and they reenacted their winning lip-lock onstage in front of screaming fans. Gosling, in a DARFUR T-shirt, looked like the happiest dude on Earth. They were young and famous and famously in love—recall, if you will, Saturday Night Live's "Lazy Sunday" skit, in which Andy Samberg raps about loving cupcakes "like McAdams loves Gosling"—and the degree to which strangers felt a personal stake in the relationship creeped Gosling out.

"I mean, God bless The Notebook," Gosling says. "It introduced me to one of the great loves of my life. But people do Rachel and me a disservice by assuming we were anything like the people in that movie. Rachel and my love story is a hell of a lot more romantic than that."

They broke up, is the thing. It's been a few months. Gosling says it wasn't the attention that did it, but other than that he doesn't really know what to say. "The only thing I remember is we both went down swingin' and we called it a draw," he says.

The Notebook people have taken it harder. "Women are mad at me," Gosling says with a rueful smile. "A girl came up to me on the street and she almost smacked me. Like, ‘How could you? How could you let a girl like that go?' I feel like I want to give people hugs, they seem so sad. Rachel and I should be the ones getting hugs! Instead, we're consoling everybody else."

He can feel his public persona taking on a life of its own. Things get polluted.

Take the band. It was one of the first things we talked about. It's a duo—Gosling and a friend, who I later figure out is McAdams's sister's ex-boyfriend—and there's at least one MP3 of their stuff kicking around online which sounds a little like Tom Waits and a little like depraved New York gypsy-punkers Gogol Bordello and is surprisingly good. Gosling talks about it like they're just fooling around, but he also mentions that he and his partner just got back from Israel, where they recorded with local musicians, which is a long way to go to fool around.

The day after I meet with Gosling, his manager calls. I'm expecting it's going to be about the Rachel stuff; instead, she asks me if I could maybe not make a big deal about Gosling's music or where it can be found on the Web, this being an early and delicate stage of the band's existence. (She then adds "They're talking to labels," lest I think the band a secret not worth keeping.)

You can see why Gosling's nervous. The minute his name's attached, the band becomes an actor's band, an arrogant presumption of transferable skill. It becomes Dogstar (Keanu Reeves, bass.) This is going to happen no matter what, and Gosling has to know that, but for the moment it still belongs to him, it's still a real thing.

Usually you make a movie like Lars and the Real Girl when you want to slow up or entirely derail your burgeoning movie stardom. Gosling gained weight for the part—he looks winter-tubby, like a South Park kid grown up weird. He sports the least virile mustache you've ever seen. Oh—and Bianca, his love interest, is a Real Doll. One of those life-size, fully-and-they-mean-fully articulated silicone lady friends. As discussed—and horribly abused—on Howard Stern.

Lars orders her off the Internet, and when she arrives in the mail he speaks to her like a real person, pushes her around his little mountain town in a wheelchair, takes her to church. The film is deliberately ambiguous as to whether or not any actual man-doll congress takes place, and when asked about this aspect of the story, so is Gosling, but the idea that Lars is maybe putting Bianca to the use she was built for is a constant undercurrent in the film.

You can imagine a professional weirdo like Crispin Glover pitching this movie to studio execs: the nervous smiles, the smooth reach for the security-call button. And yet Lars is actually a surprisingly tender and traditional romantic comedy—it's easily the sweetest thing Gosling's done since The Notebook. You keep waiting for a dark turn that never comes—for a graphic scene that rubs your face in the creepy physical realities of doll-fucking, maybe, or for the conservative, religious townspeople who've agreed to treat Bianca the way Lars treats her to change their minds and reach for the torches. Instead, the weirdest thing about the movie turns out to be the gentleness with which it treats its characters.

"I cried at the end, when I read it," Gosling says. "I just thought it was so romantic—the idea that you don't need to be loved in return in order to love something or someone. Love can come from you. It doesn't have to be reciprocal. People love their cars. People love all kinds of things, and they really love them. And we don't really value that kind of love because it's not a real, reciprocal kind of love, but it's real love to them."

"You probably hear this a lot, but he was my first choice," Lars director Craig Gillespie says of Gosling. "He's got this innocence about him and this incredibly receptive face—everything in his eyes is positive and optimistic. I felt that's what Lars was."

"There was a real respect for the doll on the set," says Emily Mortimer, who plays Lars's sister-in-law in the film. "Like, no one was allowed to make jokes about her or stick things up her nose. I mean, you can imagine the temptation, with someone or something like that around, to stick a cigarette in her mouth and put sunglasses on her, or worse. But Ryan was extremely careful with her. There was something rather amazing about that, because it was so bizarre, but very sweet, and it dictated the attitude of everybody in the movie and on the set to this thing. They gave her the same respect you would give anyone."

"I always felt rather guilty," Mortimer says. "I don't know whether I should say this, it's like I'm giving myself away, but I always felt like I was faking it with Bianca. I'd be trying to impress Ryan by paying attention to her when we weren't acting. I was pretending, trying to make him think I was cool."

Gosling's getting antsy. He needs to walk and to smoke. We end up sitting on a bus bench, at dusk, across the street from the Hollywood Royale Guest Home.

As we watch the shuffling shapes of retirees behind the shades. I ask him about something Nick Cassavetes said about him once, that he was 23 going on 63.

"That's almost insulting," Gosling says, laughing. "I liked being young. I just didn't like the idea that I couldn't be in control of my day. The fact that there were all these people that were in charge of my day was something I couldn't get my head around. It got me into a lot of trouble.

"I just wanted to have more control over my life," Gosling says. "And I thought the entertainment business, being an actor, seemed like the answer. It seemed like you make lots of money and nobody tells you what to do. I didn't realize that, with the kind of movies I was going to make, I wasn't going to make a lot of money and everyone was going to tell me what to do."

I ask him what he's going to do tonight.

"I have no idea," he says, flicking a butt into traffic. "You need a ride somewhere?"

We walk back to the coffee shop, to where Gosling's black Prius is parked. Then we're bombing through Hollywood, Gosling smoking out the window, dialing up classic rock. We are somewhere on Sunset when—swear to God—"Light My Fire" comes on. It's like the ghost of Jim Morrison is haunting us, threatening to read his poetry aloud.

"Maybe," Gosling says, "we should just submit to it."

He turns the radio up. Floors it through a yellow light. Tries to set the night on fire.

Alex Pappademas is a GQ staff writer.